President Woodrow Wilson created the first Armistice Day in 1919 to mark the anniversary of the end of World War I, November 11, 1918. During the 1920s, successive presidents made annual proclamations for observing November 11 with appropriate ceremonies. Armistice Day became a legal holiday in 1938, designed to honor veterans and the cause of world peace.

(LOC)

(LOC)

The peace did not last. After World War II ended in 1945, a movement started for a designated remembrance of all veterans. Congress passed legislation in 1954 substituting Veterans Days for Armistice Day. Beginning in 1971, because of the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, official celebrations of Veterans Day were moved to the fourth Monday in October.

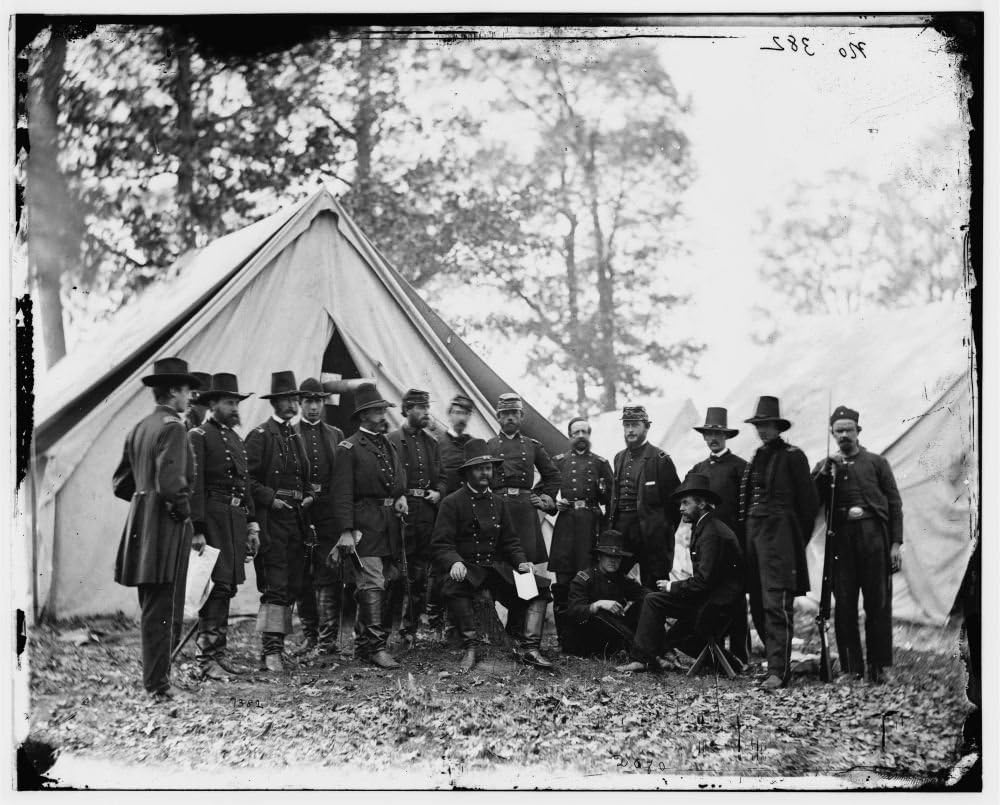

Before the two world wars, the United States had been involved in its own Civil War. A year after that conflict ended in 1865, the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) formed to provide fellowship and support for Union veterans. The GAR also organized the earliest Memorial Day celebrations and supported federal pensions for veterans.

The GAR extended membership to at least two women: a vivandiere from Rhode Island named Kady Brownell and Sara Emma Edmonds, who dressed like a man to join the 2nd Michigan Infantry.

Though no evidence exists that she was a member, Dr. Mary Walker attended many GAR events, including one in Steubenville, Ohio in 1879. Her employment as a contract surgeon with the 52nd Ohio was as close to military service that she could get during the Civil War. After the war, Dr. Walker frequently received letters from men she had treated or met. If they were in need of assistance, she always tried to help.

About 6200 veterans marched in a parade in Steubenville on August 28, 1879. Twenty-five thousand people crowded into the city to take part in the festivities. Many belonged to area GAR posts. Dr. Walker sat on the bandstand platform, surrounded by politicians and generals, to listen to speeches. Local newspapers referred to her as a “veteran”–with the word carefully bracketed by quotation marks. She felt honored.

(LOC)

(LOC)

As Civil War veterans aged and died, membership in the GAR dwindled. It dissolved in 1956, after the death of its last member.

(LOC)

(LOC) (LOC)

(LOC)