Way back in the spring of this year I traveled to Washington, D.C. It was a multi-purpose trip. I wanted to attend the annual conference of the Biographers International Organization (BIO). I have been a member for several years and have met, mostly online, many wonderful and talented writers. This would be a chance to see some of them in person and to learn new things about writing biography.

And while in D.C., I could do some research at the Library of Congress in two collections that I thought might have some useful information about Jane Grant: the papers of author Marcia Davenport and the records of the Writers’ War Board (WWB).

The third reason was just as important: sightseeing. Charles and I hadn’t been to D.C. in a very long time and it’s one of our favorite cities. I hesitated a bit because of the presence of the current administration but then worried that because of the current administration, the things we enjoy seeing might not be accessible for much longer. (I was right to be concerned. The recent government shutdown caused the Smithsonian to close its doors.) So off we went.

It was a marvelous trip. We visited many of the Smithsonian museums and various monuments, we ate at very good restaurants—our favorite was probably Immigrant Food at the White House on Pennsylvania Avenue. The BIO conference was illuminating, and I enjoyed meeting other biographers. I hope to attend another soon, especially when it’s back in its usual New York City location, because then I can add some more Jane Grant research to my itinerary.

(Immigrant Food at the White House, 1701 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, via Tripadvisor)

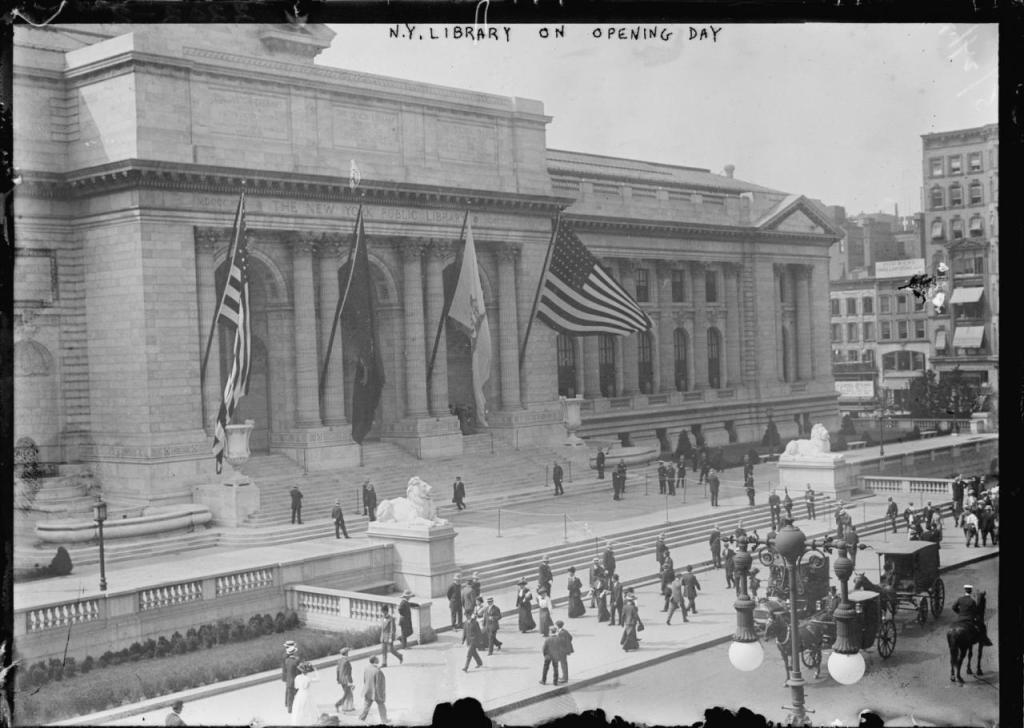

About the second reason for the D.C. trip: archival research. I ended up not needing all the time for it that I blocked off. On the one hand—yay! More time for museums. On the other—rats! Nothing new about Jane. I knew it was a gamble going in, but a historian always hopes to get her eyes on something stunning. Or at least interesting. Mostly, though, the visit to the Library of Congress served as a sharp reminder of archival absences, what gets saved and preserved and what gets, for one reason or another, tossed.

(Library of Congress, Main Entrance of the Thomas Jefferson building, Billy Wilson, Flickr, 2022, NPS.gov)

During World War II, Jane served as the editor of the WWB’s newsletter. The board was a volunteer organization that helped the government produce well-written propaganda in support of the war effort by matching writers with issues the government and military wanted to highlight. The WWB’s records provided a lot of information on how this worked, but nothing about Jane’s role that I didn’t already know from the documents she saved and are with her papers at the University of Oregon.

I knew from the collection description of Marcia Davenport’s papers that they focused on her writing career—that there would be a lot about her public life and maybe nothing about her private life. The second part proved true. Since she and Jane were friends for many years, I’d hoped that some of their personal correspondence might have sneaked in. But Jane is as absent in the collection as she is in Marcia’s 1967 memoir Too Strong for Fantasy. (To be fair, Marcia does not appear in Jane’s memoir, either. But Marcia’s book covers the time period during which their friendship was the most active, and Jane’s does not.)

Jane first knew Marcia Davenport as Marcia Clarke. Before that, she was Abigail Marcia Glick, born in New York City in 1903 to Reba Feinsohn Glick and Bernard Glick, who worked in insurance. The Romanian-born Reba, twelve years younger than her husband, began formal singing lessons as an adult, taking her young daughter with her to Europe for her summer studies. Within a few years Reba was performing at the Metropolitan Opera under her stage name, Alma Gluck. Marcia’s parents divorced in 1911, and she started using the name Gluck instead of Glick, so throughout her life she was known, at different times, as Glick, Gluck, Clarke, and finally Davenport. Three years after the divorce, Alma Gluck married Ephrem Zimbalist, a concert violinist. (Alma then gave birth to Marcia’s half-brother, Ephrem Zimbalist, Jr., who went on to become an actor, probably most known as the lead in the 1960s television show The F.B.I., and the father of Stephanie Zimbalist, who in the 1980s co-starred in the marvelous Remington Steele with Pierce Brosnan.)

(Alma Gluck and daughter Marcia, c. 1915, Library of Congress)

Growing up, Marcia was surrounded by classical music and classical musicians. She had also become, by her own admission, a “spoilt brat.” Her mother sent her to live with the Earl Barnes family, friends of friends, in Philadelphia where she attended a Quaker day school. From there, Marcia enrolled at Wellesley College in 1921 but failed to graduate. During the summer of 1922, while taking some courses at the University of Grenoble in France, she met Frank Delmas Clarke, who was from New Orleans and a student at Yale University’s Sheffield Scientific School in New Haven, Connecticut.

They fell in love. Both returned to their respective colleges in the fall but hated being apart. Marcia, who had not done well during her freshman year, knew she was in danger of flunking out. Clarke was not happy with his program, so they decided to get engaged. Clarke dropped out of school, and a relative secured a position for him in the coal business in Pittsburgh. Marcia and Clarke married on April 22, 1923, in Port Chester, New York, before moving to the Steel City.

The next year, Marcia gave birth to a daughter. Clarke relocated the family to Philadelphia, where he had taken a new job, then walked out on them after a few weeks. Suddenly a single mother, Marcia scrambled to land a job as a copywriter for a local retail store. She enjoyed the work and thrived on it, appreciating the independence it afforded her. In 1927, she returned to New York City to pursue a job as a writer.

Vanity Fair editor and friend of the family Frank Crowninshield arranged an introduction to John Hanrahan, business manager at The New Yorker. Since Marcia lacked any real journalism experience, Crowninshield thought Hanrahan would be more likely to see the potential in her advertising copy portfolio. It would at least get her a foot in the door at the magazine.

The strategy worked. Hanrahan put in a word for Marcia with Harold Ross, and she was asked to write an article, on speculation, about a new apartment house that was going up. “The assignment was like handing a porterhouse steak to a hungry hound,” Marcia recalled in her memoir. “I was hired immediately as a general staff writer. My basic work was as a reporter for ‘The Talk of the Town.’ My job was leg-work, gathering at its sources the material which the rewrite geniuses turned into the front-of-the-book.”

Soon, in addition to her “Talk of the Town” work, Marcia was writing five columns under different pseudonyms. She later remembered that this frenetic activity was not unique to her. “We all worked as hard. We thought nothing of working from early morning until nine or ten at night, with a sandwich for lunch at our desks. Then after a dinner break the proofs would start coming in. They had to be corrected and rewritten in whole or in part after Ross got his hooks into them, so it was the rule rather than the exception to work from eleven or twelve at night until dawn.”

It’s not clear exactly when Jane Grant met Marcia, but it was likely not long after she started at The New Yorker. If the two women didn’t run into each other during one of Jane’s rare visits to the magazine’s office, Ross might have made a point of mentioning Marcia to his wife. The women had a lot in common: music, opera, journalism. It is likely that Jane invited Marcia to the brownstone for dinner at least once, maybe more often.

In 1929, the year Jane and Ross divorced, Marcia remarried. Russell Davenport was a Yale graduate and an aspiring novelist and poet from an influential Philadelphia family. Marcia Davenport left The New Yorker about a year later to focus on writing a biography of Mozart, which was published in 1932 by Charles Scribner’s Sons and remained in print for decades.

During the 1930s, when Jane traveled extensively through Europe, she and Marcia joined up for at least part of her journey. They got along so well that once, after they parted from their travels in the summer of 1937, Marcia wrote to Jane, “I can tell you with the utmost truth that the best part of the summer for me was our trip, even with the trials of Albania, and that Athens remains the high point of my experiences for a long time past.”

Their friendship may have continued beyond the late 1930s, after Jane stopped taking European vacations. Fascism had been on the rise and World War II was about to break out. William Harris, the man Jane was seeing in the 1930s and would later marry, took a job at Fortune in 1937, the same year Russell Davenport became the magazine’s managing editor, so the two women had that connection as well.

Marcia Davenport’s writing career took off in the 1930s. She worked for a few years as the music critic for Stage magazine, which had a financial connection to The New Yorker. She penned two best-selling novels in the 1940s: The Valley of Decision, a multi-generational family drama, and East Side, West Side, a story of the unraveling of the marriage of a New York City couple. Both became big-budget MGM movies; the first starred Greer Garson and Gregory Peck, the second James Mason and Barbara Stanwick.

(Marcia Davenport at NBC radio, 1936)

So far, I have found no evidence that Jane read either of the novels or saw the movie versions. But I will be making another research trip to the University of Oregon for another look through Jane’s papers. I did not have enough time to turn over every page during my first trip, but one of the things I want to keep an eye out for on my next visit is additional information about the Jane/Marcia friendship. It may exist. It may not. That’s all part of the research life—finding the conversations and confronting the silences.

Now that December is here, it’s time to draw to a close The Year of Jane Grant. My work on the Jane Grant book will continue into 2026, so stay tuned for updates on its progress. The first posts of 2026 will likely be my annual roundup of my favorite books from the past year, something I love to share.

Until then, happy holidays!

You must be logged in to post a comment.