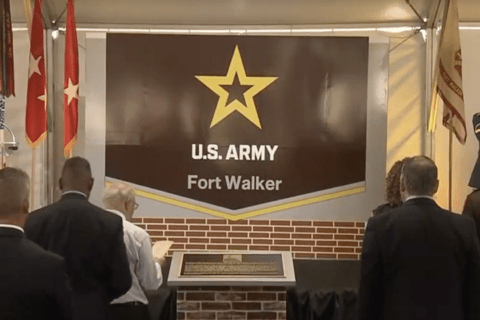

On August 25, 2023, with modest fanfare, the U.S. Army’s Fort A.P. Hill, located south of Fredericksburg, Virginia, near the town of Bowling Green, became Fort Walker. Dr. Mary Walker, who served the army as a civilian surgeon during the Civil War, remains the only woman to have received the Medal of Honor. Now she is the only woman to have a military installation named solely in her honor.*

(photo: Fort Walker on Facebook)

But that honor originally belonged to Ambrose Powell Hill, Jr., a native of Culpeper, Virginia. Born in 1825 to a family that held enslaved people, Hill graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1847 and served competently enough to earn a promotion to first lieutenant in 1851.

As politicians in Virginia debated secession following Abraham Lincoln’s presidential victory in 1860, Ambrose Hill resigned his U.S. army commission. He signed on as a colonel with the 13th Virginia Infantry Regiment when Virginia seceded from the United States. He became a brigadier general in 1862 and was promoted to lieutenant general in 1863. During the battle of Petersburg, a week before the end of the war in 1865, Hill was shot dead by a soldier of the United States army.

(photo: U.S. National Park Service)

A.P. Hill did a lot of things in his military career before and during the Civil War. Several websites provide details of his service, there is a lengthy YouTube documentary that labels him the Confederate Warrior, he appears in numerous books about the war, and he is the subject of at least two published biographies.

But the most important thing to know is that A.P. Hill served the Confederacy. He chose to renounce his allegiance to the United States and to make war on its people. Yet some eighty years later, his name was attached to a U.S. military installation. This was made possible because, as historians such as Karen Cox and Adam Domby have shown, white southerners successfully promoted the myth of the “lost cause”—that their forebears nobly fought the Civil War to protect their homes and families.**

Another eighty years later, in response to waves of racial justice activism, Congress established in 2021 the Commission on the Naming of Items of the Department of Defense that Commemorate the Confederate States of America or Any Person Who Served Voluntarily with the Confederate States of America to oversee the removal of Confederate names from property owned or controlled by the Department of Defense. The Naming Commission solicited recommendations for the nine designated military installations and narrowed the suggestions to ninety names. Several women appeared on the list, but it was dominated by men.

Still, Dr. Mary Walker made the final cut, and it is particularly fitting that an army post in Virginia now bears her name. In 1861, during the first year of the Civil War, Mary Walker, an 1855 graduate of the Syracuse Medical College, shuttered her private medical practice in New York and traveled to Washington, D.C. She failed to convince the secretary of war to commission her as a surgeon in the U.S. army, so she volunteered at the city’s Indiana Hospital, run by Dr. J.N. Green of the 19th Indiana Volunteers, who recognized her medical credentials and gratefully allowed her to work as a doctor.

Dr. Walker expanded her services into Virginia, tending to General Ambrose Burnside’s Army of the Potomac in the wake of the 1862 fighting at Fredericksburg. She treated men at Gettysburg and Chattanooga in 1863 before receiving a contract as a civilian surgeon for the army.

Confederate soldiers in northern Georgia arrested Mary Walker in 1864. She was posted at the time with the 52nd Ohio Volunteers at Lee and Gordon’s Mills and had been out in the surrounding countryside tending to sick civilians. The enemy soldiers found her activities suspicious. (Indeed, she was also gathering intelligence.) Dr. Walker spent several months as a prisoner of war in Castle Thunder in Richmond, Virginia, and gained her release through a prisoner swap.

(image: F. Dielman, artist; F. E. Sachse & Company, lithographer)

She went right back to work for the army, accepting an appointment at the Female Military Prison in Louisville, Kentucky. Dr. Walker may have expressed sympathy over her patients’ medical ailments, but she meted out punishment for their disloyal talk about the United States and their insistence on singing Confederate songs. During her final contract weeks at a refugee hospital in Clarksville, Tennessee, in the spring of 1865, Mary Walker caused a scene during Easter Sunday at the Episcopal Trinity Church when she interpreted the color scheme of the minister’s holiday decorations as too Confederate.

A few months after the Civil War ended, guided by the recommendations of the secretary of war and the judge advocate general who lauded her contributions to the army, President Andrew Johnson awarded Dr. Mary Walker the Medal of Honor.

(photo: Library of Congress)

Dr. Walker’s opinion of Confederates did not soften with their defeat. While in Paris attending the 1867 Exposition Universelle—a world’s fair—she was physically ejected from one of the United States exhibition halls. She resented a display of photos of Confederate generals, especially the one of Robert E. Lee. Its caption, she believed, was entirely too flattering. The American organizers ignored Dr. Walker’s complaint, so she tore down the caption card, prompting her swift removal.

It’s not hard to imagine how Mary Walker would have reacted to seeing the U.S. military name some of its installations after traitors of her country. She would have had no truck with “lost cause” sentimentalities. She would have known that those Confederate names did not belong on those establishments. She would have known that her name did.

(photo: see below)

*The former Fort Lee, also in Virginia, was renamed Fort Gregg-Adams, to honor Lieutenant General Arthur Gregg, the first Black man to achieve that rank, and Lieutenant Colonel Charity Adams, the first Black woman officer in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.

**Anyone interested in the history of the “lost cause” myth and how it has reverberated through history should read Karen Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture as well as her No Common Ground, Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice; and Adam Domby, The False Cause: Fraud, Fabrication, and White Supremacy in Confederate Memory.

Sources:

Suggested readings:

Theresa Kaminski, Dr. Mary Walker’s Civil War: http://lyonspress.com/books/9781493036097

Karen Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: https://upf.com/book.asp?id=9780813064130

Karen Cox, No Common Ground: https://uncpress.org/book/9781469662671/no-common-ground/

Adam Domby, The False Cause: https://www.upress.virginia.edu/title/5354/

You must be logged in to post a comment.