In my quest for a new-to-me Christmas-y movie, I finally watched Holiday Inn. I have always known that White Christmas was based on Holiday Inn, and I’ve seen White Christmas (the “Sisters” acts are perfection, and Doris’s comment, “Well I like that! Without so much as a ‘kiss my foot’ or ‘have an apple’,” is snortingly funny) too many times to count. It is one of the few musicals I will watch without fast forwarding through the song-and-dance numbers. (Yes, not a big fan.)

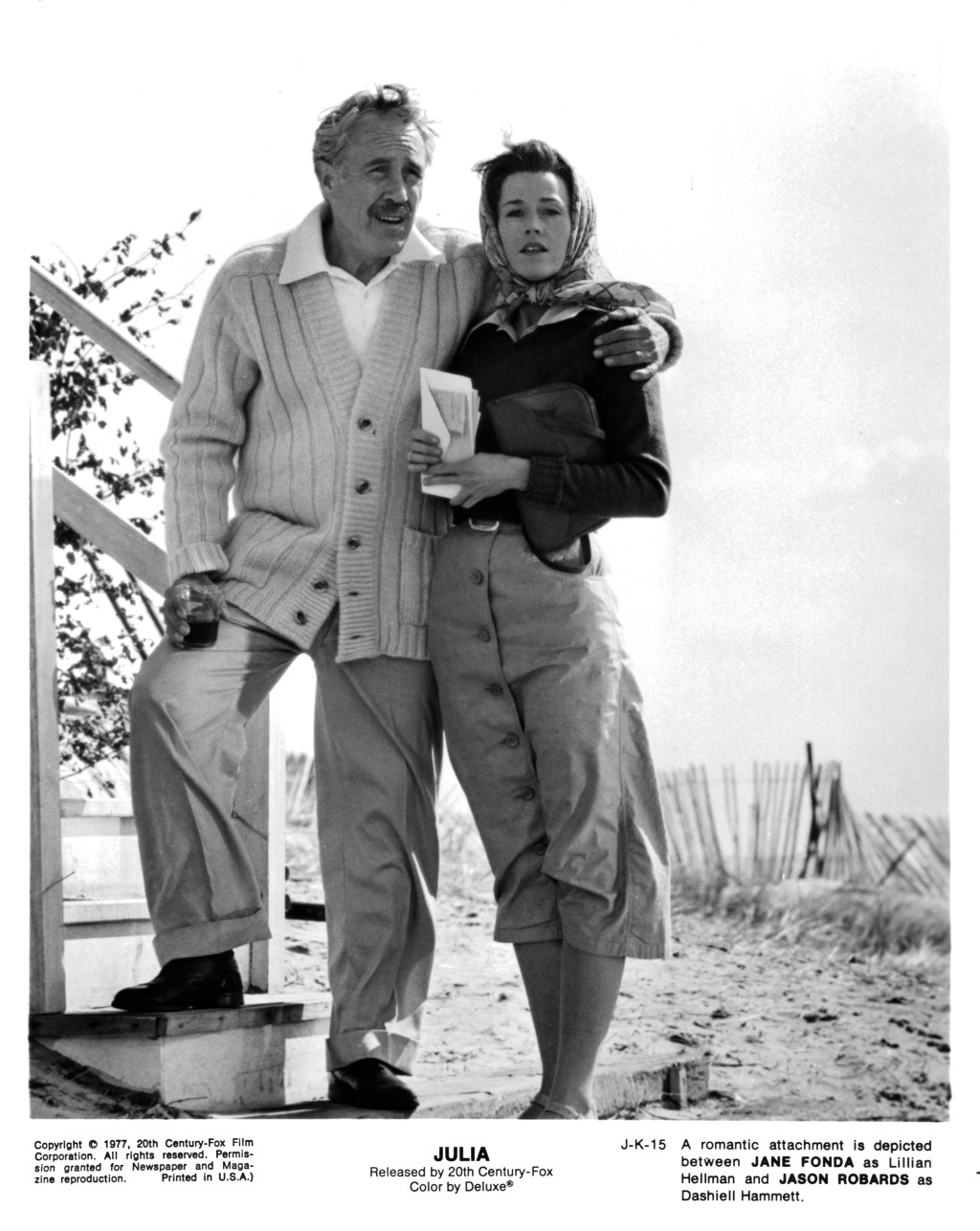

The 1942 Paramount Pictures musical Holiday Inn starred Bing Crosby as Jim Hardy and Fred Astaire as Ted Hanover. They have a singing and dancing act with Lila Dixon, played by Virginia Dale. After Jim’s engagement to Lila fails (she throws him over for Ted), he moves to a farm in Connecticut that he decides to turn into an inn that will only open on holidays. Aspiring entertainer Linda Mason (played by Marjorie Reynolds) shows up at the farm intent on getting a job, she and Jim sing “White Christmas,” and he falls in love with her.

All sorts of other things happen—there is a whole lot of plot here stretched out to link the many musical numbers—before another round of “White Christmas” and the happy Hollywood ending. I did my usual fast forwarding, though I have always enjoyed Crosby’s smooth voice and appreciated the genius of Astaire’s fancy footwork. Also, the racist elements (especially the blackface performance of “Abraham”) and the sexist attitudes (too numerous to mention) of the story make many of the scenes cringe-worthy.

I was particularly interested in Marjorie Reynolds’s performance. She had trained as a dancer and began appearing in silent films when she was a child. The 1930s found her in bit parts in several movies at the big Hollywood studios, including a small role in MGM’s Gone With the Wind in 1939. Reynolds did not turn down offers from B studios like Monogram and Republic, where, in 1941 she appeared opposite the popular singing cowboy Roy Rogers in Robin Hood of the Pecos. She was a working actor, and she likely believed her part in Holiday Inn, which put her alongside the star Fred Astaire, would quickly elevate her status.

According to IMDb, the role of Linda Mason in Holiday Inn had been written for Mary Martin, an accomplished vocalist and dancer who was already a hit on Broadway. She declined, saying she was pregnant so could not take the role. Director Mark Sandrich suggested Ginger Rogers (Astaire’s most famous dancing partner) and Rita Hayworth, but Paramount would not sign off. Sandrich would have to find someone else. Perhaps a Hollywood newcomer.

In the summer of 1941, Dale Evans arrived in Los Angeles. She had been a professional singer since the late 1920s, and over the past few years her stints on Chicago radio stations and her appearances at some of the city’s trendiest nightclubs had gained her quite a following. Joe Rivkin, a Hollywood agent, made a point of listening to Dale every week on the radio. He sent telegrams offering to represent her if she was interested in making the move into motion pictures. Rivkin pestered her to send photographs that he could circulate to casting agents. Dale finally relented, sending off some old publicity stills, and thought no more of it. She did not think she was attractive enough for the big screen. Besides, she was twenty-eight years old, much too old for a start in Hollywood.

But Joe Rivkin liked Dale’s looks and told her she would be perfect for a new musical, Holiday Inn, that was still in the process of casting. He cabled her, “Come at once,” and she did. After a quick session at the beauty salon of the Hollywood Plaza Hotel (Rivkin found Dale’s appearance disappointing in person and ordered a new hairstyle and better makeup), the agent brought his client to meet Bill Meiklejohn, head of talent and casting for Paramount.

The trio sat together in the studio’s commissary. Dale endured another appraisal. Meiklejohn found her nose too long for her chin; Rivkin reassured him that could be taken care of with plastic surgery. Then Rivkin launched into his pitch to promote his client’s talents. Meiklejohn seemed impressed. He asked Dale if she could dance. Rivkin answered for her, “She makes Eleanor Powell look like a bum!” (It is doubtful any dancer could have made Powell, considered at the time the world’s best tap dancer, look like a bum.)

Dale could not allow this lie to linger. “No, I can’t dance, Mr. Meiklejohn,” she said. “I’m a pretty fair ballroom dancer, but that is as far as it goes.” Rivkin insisted that Dale was talented enough to quickly pick up any dance routine. But the casting agent knew better. He told Dale, rather gently given the circumstances, that the female actor they put in the role would have to dance with Fred Astaire. She would have to be a top-notch dancer. Dale clearly did not have that experience. She would not get the part.

But Meiklejohn liked Dale. He admitted Paramount had a hefty roster of singers on its payroll; still, he wanted Dale to stay and do a screen test. If it turned out well, the studio might offer her a contract.

So Dale Evans missed the opportunity to sing “White Christmas” with Bing Crosby because she was not a good enough dancer to pair with Fred Astaire in Holiday Inn. Marjorie Reynolds was cast because she was a good enough dancer, but her vocals were not up to Paramount standards. Her singing was dubbed by Martha Mears. (I still think Dale would have been better.)

Marjorie Reynolds remained a working actor, appearing in movies through the 1940s and then on television in the 1950s. Dale Evans never received a contract from Paramount. But Twentieth Century-Fox offered a one-year contract, so she left Chicago for Hollywood. In 1943, Dale signed on with Republic Pictures, which immediately put her in featured roles, then, in 1944, cast her opposite Roy Rogers in The Cowboy and the Senorita. The film was a hit with Rogers’s fans, so Republic continued pairing them. Dale would become known as the Queen of the West and reach the heights of popularity many entertainers only dream of. And it may have come about from a missed opportunity.

Curious about the life and career of Dale Evans? Check out Queen of the West: The Life and Times of Dale Evans.

You must be logged in to post a comment.