Welcome to the first in a weekly (I hope) series that charts the progress of my current writing project, Invisible Me: Jane Grant and The New Yorker.

Since I have no deadline for finishing this book, the pace of progress is up to me. I’ve set goals throughout and meeting them has been greatly aided by three very supportive online writing communities. I envision this weekly series as adding another layer of accountability and cultivating another community (all of you).

I’ve been working on Invisible Me for a few years. Writing nonfiction history requires lots of time-consuming research and lots of writing, through multiple drafts. For this project, I’ve already made two major research trips, tracked down digitized online collections, and read dozens of published sources. Then I wrote an extremely bloated and somewhat blurry first draft.

After I finished, I wrote a book proposal so I could query literary agents for representation. The proposal, basically a sales pitch for the book, forced me to focus on the contours of the story, to make sure that Jane comes across as a multi-faceted person with plans and dreams, failures and successes, who has historical importance. During this past week, the last queries went out, and now I’m waiting to hear back from the agents. Or not. Many agents now don’t have the time to even send a rejection email, so if I don’t receive a response in a few weeks or a few months, it means they’ve passed. Or not. It’s fair game to nudge them once or twice before giving up.

While in agent-waiting mode, I’ll read through those first draft chapters to assess the scope of writing work ahead, to start a second, bloat-free draft. I may set an initial goal of completing one chapter per month.

Writing occupies part, but certainly not all, of my day. It’s the work part of my day. Luckily, since I’ve retired from academia, I set my own hours. I also read a lot and watch shows on various streaming services.

What I’m Reading

I recently finished a couple of nonfiction books about spies: The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland by Michelle Young and Family of Spies: A World War II Story of Nazi Espionage, Betrayal, and the Secret History Behind Pearl Harbor by Christine Kuehn. Both are good, and Kuehn’s book especially packs a lot of yikes moments.

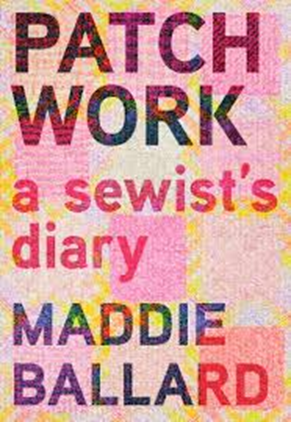

In two blissful sittings I read Maddie Ballard’s compact memoir, Patchwork: A Sewist’s Diary. I recently returned to sewing after a thirty-some year hiatus, and I loved how Ballard wrote about garment construction and identity and relationships. It’s beautiful.

And now I’m a few chapters into Palace of Deception: Museum Men and the Rise of Scientific Racism by Darrin Lunde, not at all the usual kind of book I pick up. But I’m a big fan of museums, and he presents an interesting story.

On the fiction front, I recently read Ann Cleeve’s The Killing Stone, a new Jimmy Perez story. I’m a big fan of Shetland (see below) and was happy that Cleeve brought back one of my favorite detectives, even if he’s not on Shetland anymore. I absolutely loved Sacrament, Susan Straight’s marvelous novel about nurses at a California hospital during Covid. And I continue reading (or sometimes plodding through) Vanity Fair, the 19th century classic by William Makepeace Thackeray. I’m sticking with it for an online book discussion next month. In previous years, this group has read Anna Karenina and Middlemarch, so there’s a definite vibe to these selections.

What I’m Watching

BritBox recently debuted Season 10 of Shetland, and I’m eagerly keeping up with all the episodes. Perez has moved on, but his replacement, Ruth Calder, has great chemistry with Alison “Tosh” McIntosh. I’m already looking forward to Season 11.

On PBS, there’s a new season of All Creatures Great and Small and a new mystery series called Bookish. And Paramount+ launched Starfleet Academy, the latest addition to the Star Trek universe, and it’s okay so far.

I keep meaning to watch the final episode of Stranger Things on Netflix but haven’t been in the right mood yet. I find Young Sheldon and Mom (neither of which I watched on network t.v.) reliably good, and I revisit The West Wing and The Closer from time to time.

What Else I’m Doing

Daily exercising (a portable elliptical machine is essential during winter), sewing (very sporadically lately), thrifting (one of my favorite pastimes that sometimes is related to what I’m sewing), bowling (once a week as extra exercise that’s also a fun outing).

That’s it for now. Thanks for reading. Hope you check back next week to see what kind of progress I’ve made.

You must be logged in to post a comment.