In 1941, an American woman named Gladys Savary owned and operated one of the most well-known restaurants in Manila, the capital city of the Philippine Islands. She and her French husband André, always looking for new adventures, opened the Restaurant de Paris, “Manila’s Smartest Restaurant,” in 1932. But most of its considerable clientele simply referred to it as Gladys’s, and the place filled up night after night. Almost any American living in Manila would acknowledge that everyone goes to Gladys’s.

When the war started in Europe in 1939, André left the Philippines (and his marriage to Gladys) to join the French military. Despite the European hostilities and the growing unease about Japanese aggression in the Pacific, Gladys had no qualms about remaining in Manila. “I even became a convert to the popular theory that Japan wouldn’t do any attacking of the Philippines because she could just walk into them in 1946 when Philippine independence [from the United States] would become effective.”

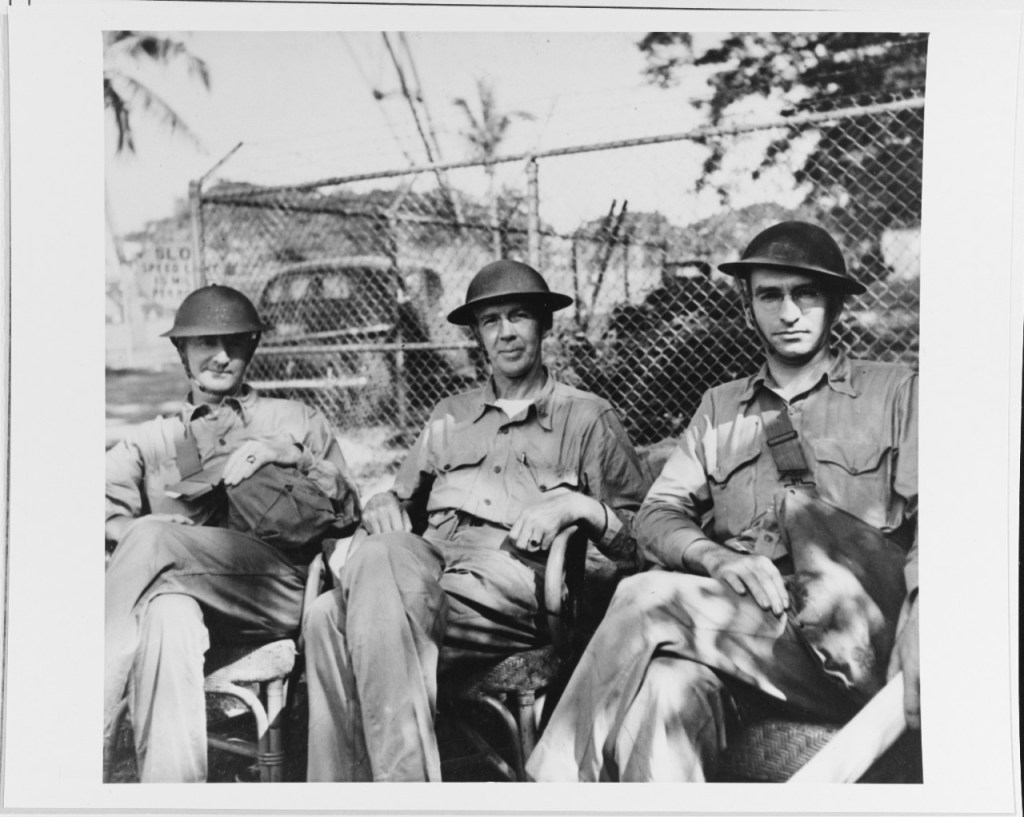

[Rear Admiral Francis W. Rockwell, USN (1886-1979), (center), Commandant of the 16th Naval District, at his headquarters after a Japanese air raid on Cavite Navy Yard, Philippines, 17 December 1941. With him are members of his staff: Lieutenant Commander Frank J. Grandfield (left) and Lieutenant Malcom Champlin. National Archives 80-G-243708]

Gladys remained hopeful into the fall of 1941, though she witnessed daily the increased activities of the military in and around Manila. She never slept on Sunday night, December 7 (Manila is on the other side of the International Date Line). She had invited some friends to the restaurant for dinner in celebration of the promotion of a British naval officer she knew. After their meal, they headed over to the Jai Alai Club to watch a match, then stopped at a nightclub before moving on to the Manila Hotel for drinks on the pavilion. Gladys and her friends concluded their evening at an all-night gambling den where they played roulette until dawn.

Gladys had no time for sleep before she needed to get out to the market Monday morning to buy the day’s food for the restaurant. Her servant Nick brought her morning coffee and the newspaper and said, “Honolulu’s bombed. What’ll we do now?” Gladys’s first thought was about business. The restaurant would be busy, she predicted, because people were always hungry. She told Nick they would do their shopping as usual. “War or no war, we have to eat. Nobody can know what’ll happen.”

Indeed, she could not know, though she may have suspected, that things would get much worse. The Japanese bombed Manila, too, and by early 1942 they occupied the city. American nationals were rounded up and confined on the grounds of Santo Tomas University. But Gladys had no intention of sitting out the war in an internment camp. She decided to evade internment and do what she could to assist those who could not. She planned to undermine the Japanese occupiers whenever possible. She risked her life and resisted.

Gladys Savary was just one of many who defied the Japanese in the fight for freedom. I think about her every year on December 7 to remember and honor the variety of sacrifices millions of people made during World War II to stop the spread of tyranny. If you are interested in finding out exactly what Gladys did during the war, read Angels of the Underground: The American Women Who Resisted the Japanese in the Philippines in World War II.

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/angels-of-the-underground-9780199928248?cc=us&lang=en&

You must be logged in to post a comment.