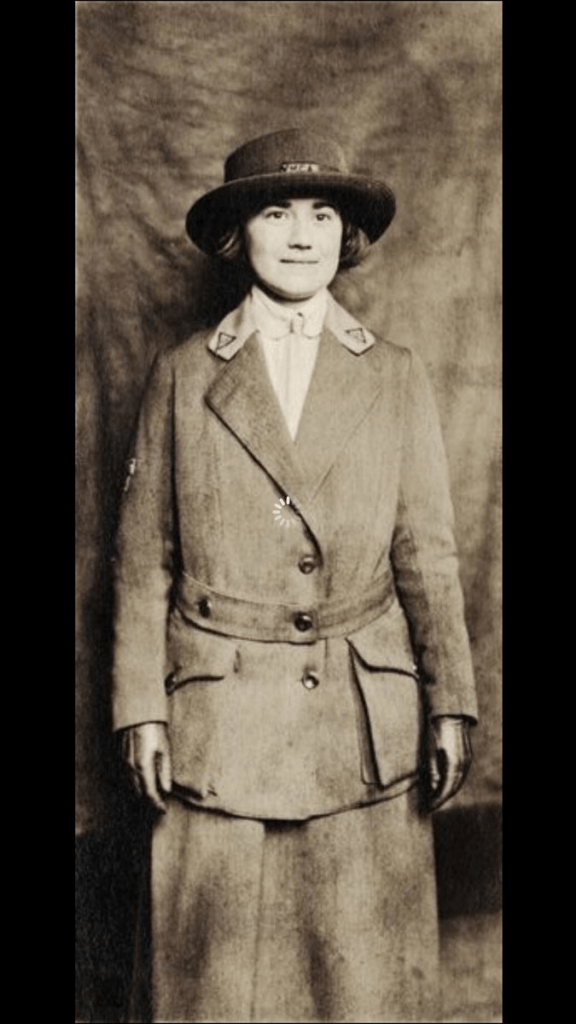

Chapter revisions of the Jane Grant book continued over this past week. Did I get as much done as I wanted? No. As I hoped? Again, no. Right now it looks like chapters two and three need to expand a bit to make room for some important historical context. I managed to answer a couple of questions I had about changes to the passport system during World War I and how the influenza pandemic affected New York City. Both had an impact on Jane’s wartime journey to France.

And I’m also thinking that chapter two needs to include something about Jane’s love life. There’s evidence that she had one well before she met Harold Ross, and I find it interesting that marriage did not seem to be her end game.

Women’s History Month

Just when I thought this would be the first Women’s History Month in recent memory that I didn’t have some kind of event planned, John Heckman, known on social media as The Tattooed Historian, invited me to appear live (!) on his YouTube channel on March 24 to talk about Dr. Mary Walker. You can find his page on Facebook, follow him on Instagram, listen to his podcast, read him on Substack, and/or watch his YouTube channel.

Here’s the information about my presentation/discussion, which bears the bold title, “She Defied Them All.”

And remember to check out Pamela Toler’s annual WHM series on her blog, History in the Margins. She runs the best Q&As with people who write or produce/promote women’s history.

What I’m Reading

I’ve started Mike Pitts’s Island at the Edge of the World: The Forgotten History of Easter Island. I probably wouldn’t have picked it up if I hadn’t seen reference to Katherine Routledge. In the book’s preface, Pitts writes, “Though I had never heard of Katherine and Scoresby Routledge, their visit was well known on the island, where it was said they had conducted the best statue survey and collected important histories. … Who was Katherine Routledge? My quest brought ever more surprises as I leafed through piles of rarely seen manuscripts in archives across England. …Why had the lifework of this woman, who seemed to have understood the place like no other outsider, vanished? The loss of this perspective mattered because, I realized, the story being told of the island’s ancient past, even today, is profoundly wrong.” (p. xviii) Of course I’m very curious to see where Pitts’s story goes.

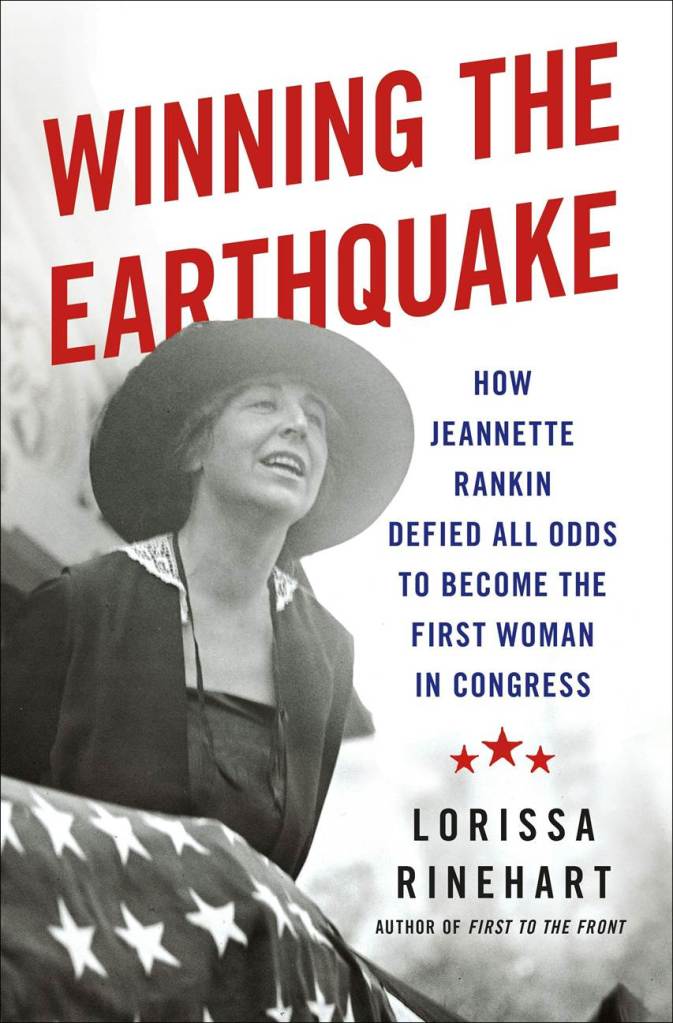

I finished Winning the Earthquake: How Jeannette Rankin Defied All Odds to Become the First Woman in Congress by Lorissa Rinehart and liked it.

What I’m Watching

I saw the first episode of the new season of Call the Midwife (PBS), and it had a couple of interesting twists.

New in the rotation are the police crime drama Hope Street (BritBox) and the quirky, comedic, kind of murder mystery How to Get to Heaven from Belfast (Netflix).

Finished The Game (BritBox), which was an effective thriller, and All Creatures Great and Small (PBS), dependably sentimental.

Saw the latest, better than most, episode of Starfleet Academy (Paramount+) and watched more of The Lincoln Lawyer (Netflix).

The filler sitcom is still Ghosts (Paramount+), and if there’s time for a filler drama, it’s been The West Wing (Netflix).

What Else I’ve Been Doing

Took a whole day away from revisions this week to go up to Green Bay. Visited the Neville Public Musuem for the first time and found the exhibits well done, especially in ways that promote learning for children. Then it was off to lunch at the Copper State Brewing Company where no beer was actually consumed, but the food was good.

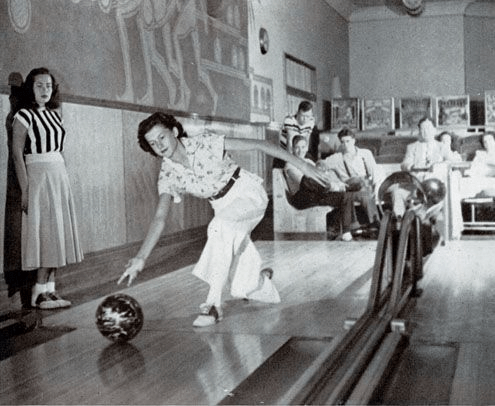

Weekly bowling, two games. Both quickly slid from mediocre to awful. That’s not the direction I was aiming for.

Finished a very small sewing project, in which I turned an outdated eternity scarf into a wraparound, making it much more versatile.

Thanks for reading. March has indeed arrived like a lamb, with slightly warmer temperatures and rain instead of snow. And now, in most of the United States, we’re headed into daylight saving time. Don’t forget to set your clocks forward. Regardless of how it registers on the clock, I’m always happy with more light in any given twenty-four hour period. See you next week.

You must be logged in to post a comment.