This week I realized that to properly revise chapter three, I needed to make some additions to chapter two. So, I’ve been reading more about the role of the YMCA in World War I to more fully explain what was expected of Jane Grant during her overseas posting and how she delivered on those expectations. That means I’ve been toggling between those two chapters to add context and additional details to sharpen the descriptions of Jane’s experiences.

I’ve made progress that seems incremental, especially when I look at how much—or little, really—the word count in each of the chapters has increased. Keeping an eye on the word count is important because I don’t want the manuscript to get bloated. Telling Jane’s story doesn’t require a Big Book in terms of the number of words and pages.

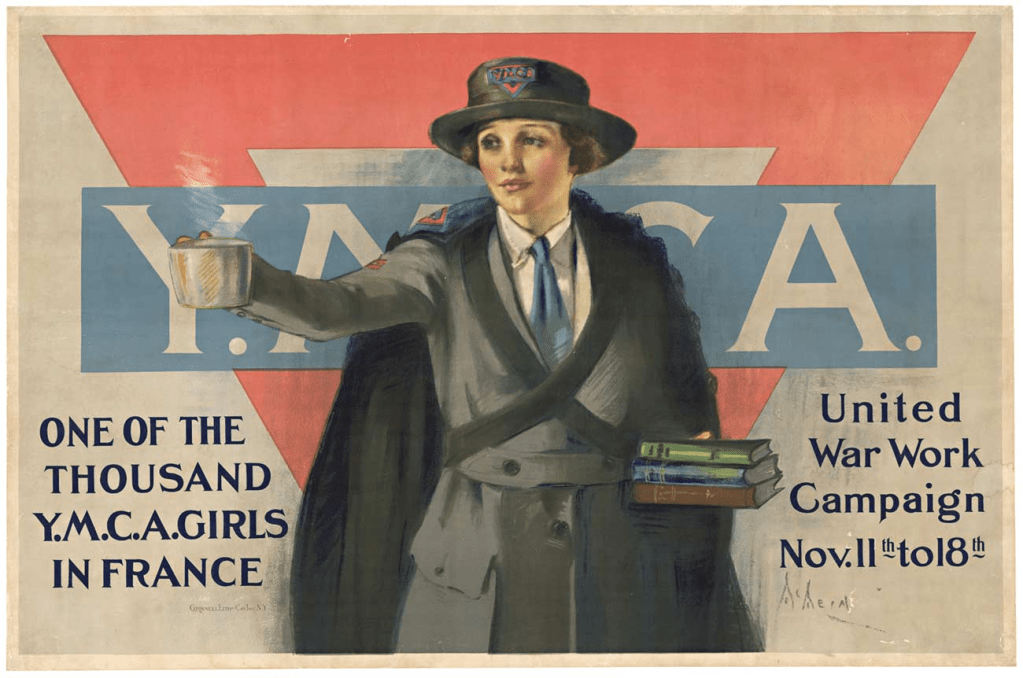

The 1918 poster below features the artwork of Neysa McMein, who also went overseas during the war to entertain the troops. She and Jane were friends.

What I’m Reading

I’m more than halfway through Angela Flournoy’s The Wilderness. It had a strong start, but now I find it very uneven. I’m looking forward to seeing how it all wraps up.

I’m almost done with Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife by Francesca Wade. Stein has died and Toklas, in her grief, is trying to carry out her wishes for her unpublished work and trying to protect her reputation as a pathbreaking author. I really like this book.

Wednesday night’s Vanity Fair Zoom book discussion was fascinating. I can’t wait to find out what the 2027 novel will be.

What I’m Watching

Nothing new in the rotation of Starfleet Academy (Paramount+), Grace and The Game (BritBox), All Creatures (PBS), and The Lincoln Lawyer (Netflix). Down to one episode left of both The Game and All Creatures. It kind of seems like The Lincoln Lawyer may never end, but I’m only at the halfway point. Last week’s Starfleet was one of the better episodes, and I hope this week’s can at least match it.

What Else I’ve Been Doing

I finished my review of the book proposal for an academic press and submitted it before the deadline. So yay me, and yay for the press that will be getting a good book—if that’s how the rest of the process works out.

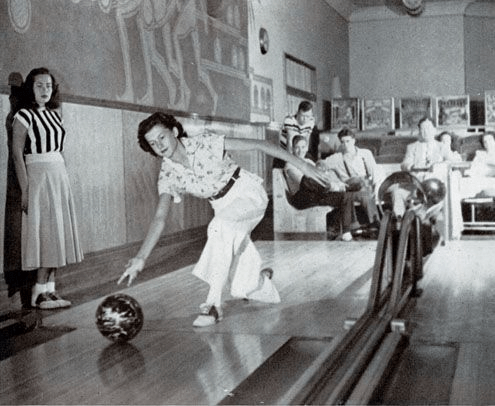

The weekly bowling took place, the usual two games. Once again it was two pretty mediocre games for me. But this week’s bright spot was that twice in one game I picked up a spare from a split. That was quite astonishing.

A couple of days after I switched out my winter walking boots for regular sneakers (thanks to warmer temperatures and nearly snow-free streets) to take my daily walks, winter sent about 6 inches of snow as a reminder that it’s still, well, winter. Not that I actually packed away the boots for the season….

Thanks for reading. Stay tuned for next week: Are chapters two and three finally revised? Are the winter walking boots still out?

You must be logged in to post a comment.